“Disappointed.”

That was the emotion I heard applied to one particular portfolio performance recently. Since February 2020’s stock market peak, the headline getting S&P 500 is higher by close to 25%. When the S&P 500 dropped more than 34% between February 18th and Mar 23 of 2020 and balanced and diversified portfolios were down by only about 1/4 of that, investors were “thrilled”. Time sure changes things. What you don’t see in the headlines is that over that same February 2020 until now time period, the Canadian Dollar is approximately 10% stronger, shaving the performance of the S&P 500 in Canadian Dollar terms by that amount, which matters if you live in Canada and spend Canadian Dollars on your lifestyle. Even more interesting is that High Rock’s balanced tactical portfolios have had solid performance so far this year (more a function of the tactical and less so of the balance). As an aside, if a client wants S&P 500 returns, we can create portfolios to catch those, however, you must be prepared to accept the potential volatility that comes with it. Not necessarily recommended for the folks who can’t tolerate big swings in portfolio value. We are always happy to discuss the risk and return equation.

Nonetheless, soul searching ensues: even though by all measures, the “disappointed” are on track to reach their previously established long-term goals as set out in their original wealth forecast. So the soul searching, in turn, brings about the question of “are we doing the right thing?”. Inevitably, the soul searchers look at the alternatives for comparison. If you do read these blogs from time to time, you will know that at High Rock, we manage risk first: our primary goal is to protect our and our clients capital so that we can work our way to ensuring that our long-term goals are met. Sometimes that means that a riskier approach to investing may out-perform what we do over shorter periods of time, especially when the headline stock markets make record highs despite questionable valuations. Over longer periods, the clients who have been with us the longest, will attest that they are on track.

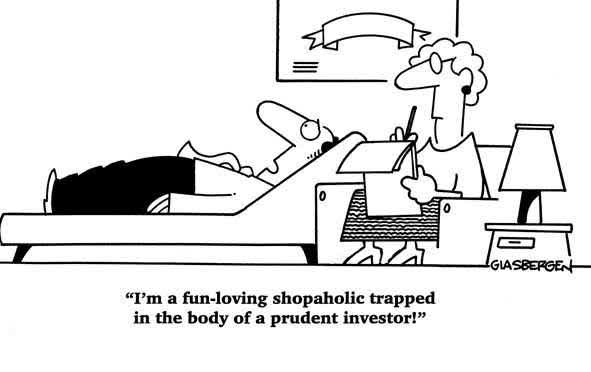

Behavioural Finance, which brings the human psychological condition into the investing equation, suggests that our emotions can and will infiltrate our decision making processes. We see something better (or are led to believe it is better) than what we currently have and want that one (perhaps so we can feel less disappointed).

As you regular readers may know, because we manage risk first, we need a discernable way to measure risk. For this we use historical data that can tell us how far an investment has deviated from its mean (or average) in times of duress. That allows us to at least understand the potential downside to every asset that we own in a portfolio.

We also know that past returns do not guarantee future performance, so we are left to add probabilities to future outcomes in order to make our assessments of risk. However, without a crystal ball to give us a more exact idea of what the future holds, the timing of the probable outcomes becomes unclear. That is why trying to determine if you have the optimal portfolio (for reaching your long-term goals) at any given moment in time might be problematic. We just do not know what curve balls that geo-politics, economics, climate, health and emotions have in store for us as we move forward in time. So we hope for the best, but prepare for the worst. Which means that we have to have built-in defense mechanisms in our investment strategies.

We also build in what we consider to be realistic long-term targets that may be tend to be conservative in nature because we would prefer to out-perform conservative objectives rather than under-perform more aggressive ones.

What do the Behavioural Finance experts have to say?

I have followed Meir Statman (a Professor of Finance at Santa Clara University and a member of the Advisory Board of the Journal of Portfolio Management, the Journal of Wealth Management, the Journal of Retirement, the Journal of Investment Consulting, and the Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance) for some time now.

In one of his most recent publications for the CFA Institute Behavioral Finance: The Second Generation he had this to say:

“Fear is a negative emotion arising in response to danger, whereas hope is a positive one in anticipation of reward, but the two are similar in that control is in the hands of others, whether other people or situations. We fear the danger of a stock market crash but cannot control the outcome. We hope for a stock market boom but cannot control the outcome.”

“Good emotional shortcuts of hope and fear guide us to allocate some, but not all, of our portfolios to risky assets, such as stocks, to attain financial security. Yet emotional errors can imperil our financial security. Excessive hope can drive us to allocate too much of our portfolios to risky assets in boom times, and emotional errors of excessive fear can scare us into dumping all our risky assets in a crash.”

“Behavioral portfolios are about life, beyond money. They are about wants beyond portfolio returns. They are about expressive and emotional benefits, beyond utilitarian benefits. And they are about risk as falling short of wants, not as variance of portfolio returns.”

And concludes with:

“Markets are not efficient in the sense that price always equals value in them, but they are efficient in the sense that they are hard to beat. Investors seek to satisfy wants for utilitarian, expressive, and emotional benefits from investments and investment activities and often commit cognitive and emotional errors on the way to their wants.”

What does it all mean? We have wants and needs that we turn into long-term goals. However, we are vulnerable to committing errors (cognitive and emotional) that may hamper our ability to reach these long-term goals. From my perspective, disappointment over a short-term time frame, believing that events that have occurred recently will continue indefinitely into the future (Recency Bias), comparing our experience relative to others (although they may have different goals) and seeking out riskier options (not making “apples to apples” comparisons) in good (stock market boom) times can have an impact that may jeopardize long-term goals.

My job: to bring a more logical approach to goal setting and the appropriate risk and return equation to reach those goals. Make a plan and stick to it: assess its progress, tweak it if necessary, but be on guard for those emotional issues that may well derail it.